Function Analysis Finding function boundaries

Hey everyone!

Right now I am in the fourth and final term of this education year. It looks like I can go on studying computer science, since I passed all my exams as of now!

Introduction

In this post I will discuss a (fairly simple) algorithm I came up with half-drunk with the purpose of determining function boundaries in x86 assembly code. Right now, it is implemented in x64dbg and you can see how it works with a command called anal (short for analyze). It does not work on weird/obfuscated/Microsoft’s code, but it’s nice to have an idea where functions start and end without having to manually go through every function you are looking at.

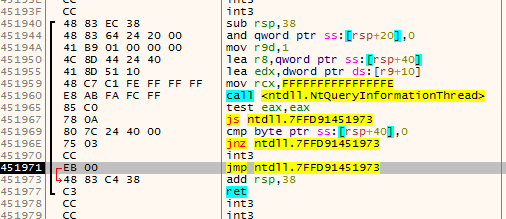

Screenshot:

The requirements

Maybe you already noticed, but x64dbg does barely use the information provided in the PE Header of a debuggee for its operations. If your executable is malformed, but can be started by CreateProcess without problems x64dbg should be able to debug it.

The downside is that x64dbg has no idea if it is looking at code, an import table, a resource table or just random data. You would have to figure that out yourself. The upside is that anything that can be run by Windows can at least be started by x64dbg.

The algorithm has a very simple input: a block of memory. The output should be a list of function boundaries. It requires nothing to work, except the virtual base address of the memory block.

The idea

After talking with various people (including cyberbob who created ArkDasm) the thing a lot of people (including our ‘competition’ at HexRays) appear to do is some kind of recursive ‘tracing’ from a certain point (usually the entry point). Basically it simulates multiple possible execution paths from that point and constructs the function boundaries from data (such as call and ret instructions) it collected on the way.

Usually I like what the cool kids on the block do, but I saw some problems:

- Recursive algorithms require housekeeping. In this case you would need to make sure data is not analyzed more than once (in case of analyzing a recursive function).

- It is hard to estimate when the recursive algorithm would end. Maybe there is only one (very small) execution path and it ends immediately, or it keeps dragging on, evaluating thousands of possible paths.

- There is no known entry point.

Now computer scientists appear to like complexity analysis of an algorithm. Probably you cannot do better than linear anyway, so I decided that I wanted to algorithm to be done in linear time O(n).

The idea I had was very simple, but it requires two assumptions to work:

- Every call destination or immediate pointing inside the memory block given for analysis is assumed to be the start of a function;

- A function ends at or after the start of that function and cannot overlap with other functions.

The first assumption should be clear to you. The second assumption might not be, but it is actually very simple: when a function starts it has to end before another function starts. This means that this system will horribly break on optimized code that places chunks of code randomly scattered throughout the memory region. Microsoft’s kernel32.dll does this for example.

Now the actual idea is to do things in two steps:

- Find all function starts;

- Figure out where functions end.

Simple right?

Finding all function starts

Doing this is actually trivial with the given assumptions! Just find any immediate that points in the memory block currently being analyzed and then sort the results and remove duplicates (a function might be called from multiple places is why). The reason for the sorting that the end cannot be further away than the next function start.

Finding the end of a function #1

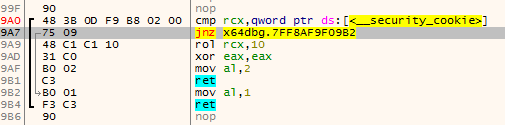

The thing that immediately comes to mind is just searching for the first ret instruction after the function start and call this the function end.

The problem with this approach is that there might be multiple exit points:

Finding the end of a function #2

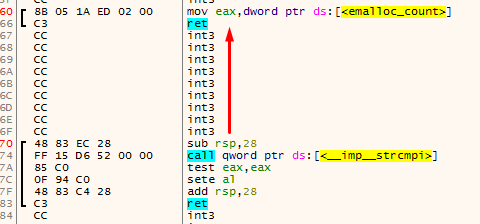

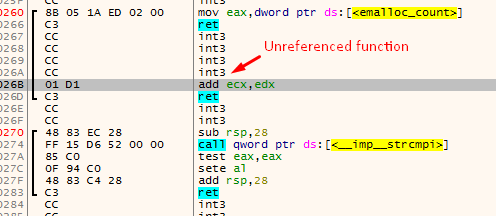

Another thing that comes in mind really quickly is just to scan backwards from a function start for the ret instruction. When found, this is the end of the previous function:

The main problem with this is that there could be unreferenced functions between the two functions that were found using the method for finding function starts. This could make really weird functions appear:

Finding the end of a function #3

The actual method I used to find the end of a function is a variation of #1. This algorithms has four cursors (the names are taken from the actual algorithm):

addris the current address being disassembled.addrwill always move forward disassembling every instruction on the way;endis the current function end (basically this is the lastretinstruction encountered byaddr);fardestis the farthest forward destination of ajxx. This will point to the farthest destination the function can go by using jumps;jumpbackis the address of the lastjmpinstruction that jumps before theendat that time.

For the understanding of the algorithm I visualized it using x64dbg. These are the colors used to indicate the various variables:

- addr

- end

- fardest

- jumpback

The first animation shows how fardest is used. When a ret instruction is encountered it is considered to be the function end if fardest has no value or points before the current ret instruction. When fardest points after the ret instruction, the algorithm will continue instead looking for another ret:

The second animation shows how the jumpback variable is used. Basically what could happen is that there is some kind of repeated structure before a function returns and that the compiler optimized this by jumping back to this structure from the end of the function (this could be done to save space for example). When the limit to where the algorithm can disassemble is reached the jumpback will be used as end of the function instead of end:

Final words

Alright, that was about it! I plan on improving this algorithm to support weird function structures done by some compilers, but the idea will stay the same (I think). I hope you enjoyed reading through this, I definitely enjoyed making it (even fixed some bugs on the way).

Greetings,

mrexodia

blog comments powered by Disqus